The Arts and Crafts Movement

In the early 90s, in limbo between fine and commercial art, I found my place in the art world when I discovered the ideals and styles of the Arts & Crafts Movement, whose revival had begun in the 70s (and which continues today).

Through tenons in a Stickley table

from a Sotheby’s publication

The Movement began in 19th century England, with the writings of John Ruskin and William Morris, who argued that the industrial revolution had produced factories that were bad for society, with terrible working conditions, pollution, and poorly made products. They advocated a more moral society, where independent craftspeople made things from design to finish, like in the guild system of the Middle Ages. In addition, they rejected the fussy, overly-decorated styles of the Victorian era in favor of more simplified, nature-inspired forms. Furthermore, Morris considered all the arts and the crafts to hold equal stature in the decoration of the home.

(I had always been troubled by the seemingly elitist and artificial distinctions between fine art and all the other visual arts: illustration, applied arts and the crafts.)

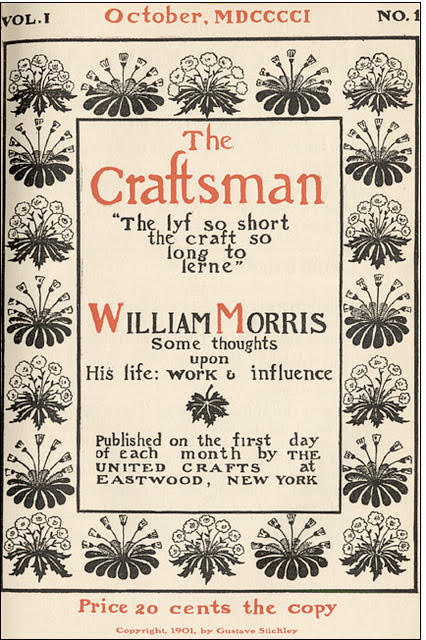

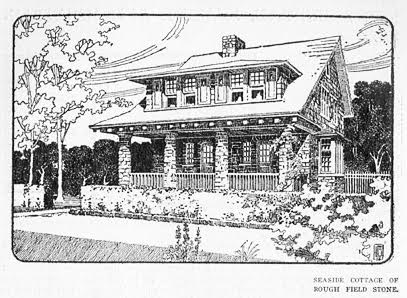

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in Europe and America, the Arts and Crafts ideals influenced architecture, painting, sculpture, graphics, illustration, book making and photography, furniture, textiles, and ceramics. In the United States, Gustav Stickley’s magazine, The Craftsman, promoted his new simpler, slightly Medieval, Arts and Crafts-influenced styles for architecture and furnishings, from which the term “Craftsman”-style was born. The new style eschewed fancy details, and instead allowed the only decoration to be the beauty of the natural materials (e.g., the grain patterns of quartersawn oak, or the texture of fieldstone pillars), and the elements of quality craftsmanship (such as through tenons and pegs in furniture, and exposed rafter tails and eave brackets in houses).

Stickley’s magazine, 1901

Exposed rafter tails and fieldstone pillars

Gus Stickley designed home

As people became swept up in these ideals, many artist colonies sprang up in Europe and America, and by 1910, “Arts and Crafts”, the “Craftsman” style, and all things handmade, had gained widespread popularity. I like to think of these folks as the hippies of their day, rejecting the soul-killing ways of the establishment and favoring a more earthy, individualistic, communal way of life.

One of the most well-known of those reformist artist colonies was Elbert Hubbard’s Roycroft.

Elbert Hubbard and The Roycrofters

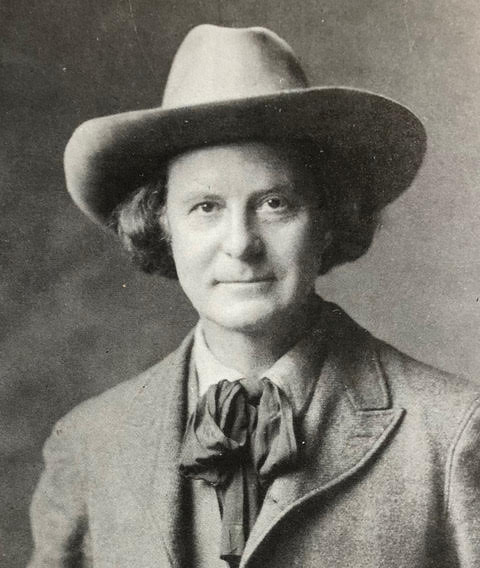

Elbert Hubbard, c. 1912

from the Elbert Hubbard-Roycroft Museum

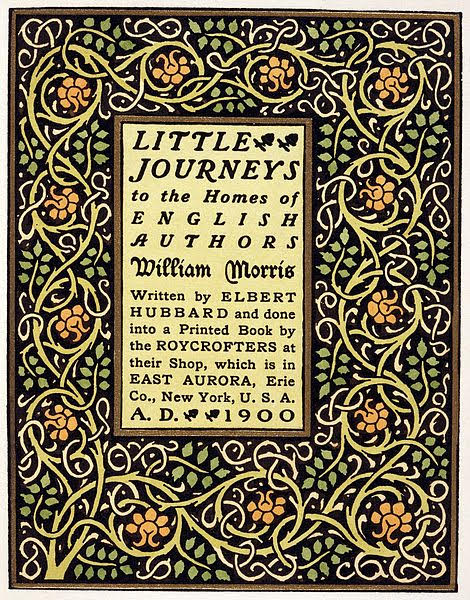

Elbert Hubbard was a soap salesman who quit the business and, inspired by a visit to William Morris’s Kelmscott Press, established an arts and crafts colony East Aurora, NY (near Buffalo) in 1895. He named it The Roycroft, meaning “craft fit for a king,” and built a campus of medieval-style buildings, where artisans made fine things such as furniture, metalwork, pottery, and beautiful books. Following Morris’s example, the Roycrofters’ books, with their hand-illumined pages and hand-tooled leather covers, were essentially art objects, meant to be appreciated for their artistry as well as their content.

Hubbard was a master salesman, and used his magazine, The Fra, to promote the goods produced on

the Roycroft campus. He was also a writer of several hugely popular books—The Little Journeys, A

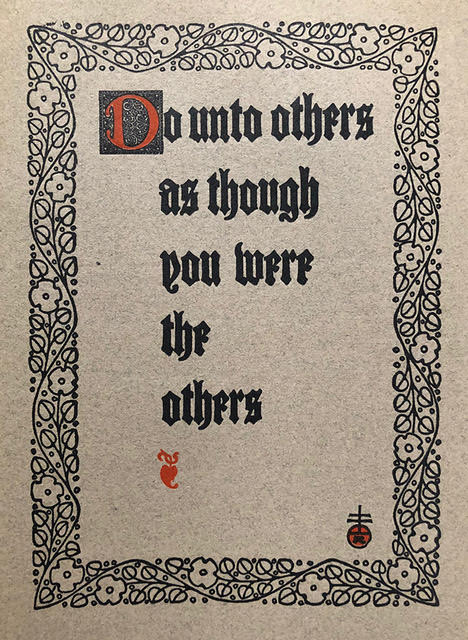

Message To Garcia, and a series of Notebooks of Elbert Hubbard, containing miscellaneous musings on

the worthwhile life, including pithy, often humorous, frame-worthy mottos, that decorated thousands of

homes.

Tragically, Elbert Hubbard and his wife, Alice, died in 1915 in the sinking of the RMS Lusitania. Elbert’s eldest son Bert took over the running of the Roycroft, until it finally closed in 1938, a victim of the depression and changing times.

The roycroft Renaissance Artisans

Inspired by the Roycroft’s principles, the Roycroft Renaissance was born in 1976, and a new community of independent artisans was established.

To become a Roycroft Renaissance Artisan, an artist must submit his/her work to a jury comprised of Master Artisans. Only artisans whose work exemplifies the following criteria are awarded the use of the RR mark:

1) High quality hand-craftmanship

2) Excellence in design

3) Continuing artistic growth

4) Originality of expression

5) Professional recognition

An artisan must be juried annually, to demonstrate continued excellece and growth. After five years, if the work is voted to be exceptional, the jury may elevate him/her to Master Artisan status.

When you see the RR mark on a piece of work, be assured it was made by a juried Roycroft Artisan to the highest standards with “Head, Heart, and Hand.”

Interior Design:

Furniture makers:

Photography:

Potters and Ceramic Tile Artists:

The RR mark on a frame means a certified Roycroft Renaissance woodworker made the frame. The RR mark on my signature means I made that piece of art. When the RR mark is missing from my signature, it means that print is a reproduction of my original artwork, printed by a professional who worked closely with me to get the color and quality right.

Here are the Roycroft Renaissance artisans, as of March 2020:

Painters, Printmakers, and Illustrators:

Book and Paper Artists:

Jewelry and Metal Artists:

Textiles:

Get more info on us, including our shows and history, on our website: https://www.ralaweb.com.